Across art, design, and digital healthcare: an interview with Associate Professor Hwang Kim

In this interview, we meet Associate Professor Hwang Kim, a pioneer in shaping digital healthcare through the lens of human-centered design in South Korea. The interview was conducted by Associate Professor Young-Woo Park on Tuesday, August 6, in Professor Kim’s office.

Young-Woo Park (YWP) I’d like to start the recording now. First, thank you for agreeing to this interview. We haven’t really had the chance to have a serious conversation beyond just having lunch together, so I think today is a great opportunity. To start with, it’s been almost five and a half years since you joined here, and I’d like to hear about the various projects and achievements you’ve accomplished during this time, as well as the vision you have for your future research.

First, when I initially looked at your various design works and research areas, I thought you had a very wide spectrum. Since coming to UNIST, you’ve particularly focused on design, health, and even design awards, pursuing these four main directions. Could you perhaps share with us what led you to focus on these areas, what inspired you to concentrate in this direction, and what influences shaped your approach?

Hwang Kim (HK) Interestingly, I majored in “Metal Art & Design” during my undergraduate studies. The Metal Art & Design Department at Hongik University from 2000 to 2005 offered a curriculum that encompassed both crafts and design. They taught metalworking, where we would melt metal to create crafted products, and at the same time, there were courses in Flash action-script within the department. At the time, I didn’t place much significance on the fact that I was majoring in crafts. However, as time passed, I realized that studying crafts had a considerable impact on me.

There’s a difference between designing based on crafts, designing based on industrial design, and scientific design, which is what UNIST pursues. Designing from a craft perspective is closer to art; it involves aesthetic and philosophical considerations. During my undergraduate studies, I learned about designing from an artistic and creative perspective. Especially after coming to UNIST and teaching scientific design, I’ve given much more thought to the academic differences between scientific design and artistic design. In art, it’s important to question existing paradigms and break away from them. There’s no right or wrong, and expressing oneself is crucial. As an undergraduate, I was taught by my professors to question, challenge, and critically view the existing artistic rules. Those educational approaches seem to have influenced me, both consciously and unconsciously.

At the same time, the early 2000s, when I was an undergraduate, marked the beginning of the digital revolution across society. People started creating email accounts for the first time (I remember setting up my first Daum email in a PC room in 1999 just to sign up for Starcraft’s battle.net), and even within the university, we realized that digital technology would shape the future of society and technology. Many clubs emerged, and students, regardless of their major, became interested in digital design. I also started coding, using Visual Basic and Action-script. However, back then, the concept of UX (User Experience) was not well understood. It was the Industrial Design Department at KAIST that began teaching the concept of UX, and Naver’s UX Design Lab published various reports on it. I was fortunate to be able to self-study UX through reports published by Naver and apply it in practice while working at Ahn Graphics. By the late 2000s, the concept of UX had become mainstream among designers, and there was a shift from an obsession with visual design to a broader focus on building websites that considered the user experience.

In 2008, I moved to the UK, and ironically, I found myself wanting to take a break from practical work and return to creating art. I faced the dilemma of choosing between pursuing something that would help with my career or doing something I wanted to do, even if just for a short while. Since I was studying abroad with significant financial debt, this was a tough decision. But ultimately, I decided to pursue the most experimental design path with the mindset of “I’ll do what I want up to this point, and then I’ll focus on finding a job.” (Some people even said that RCA Design Products was not a place for design but for art.) I spent two years at the Royal College of Art in the UK, experimenting with speculative design or critical design. There, the design work I did was less about “solving problems” and more about “asking questions.”

After spending two years at RCA, I joined Philips Healthcare in 2011. Philips Design had an innovative image in the design industry, particularly with their experimental projects in the Design Probes department. I was attracted to the long history of Dutch design, the strength of the design research field (centered around TU Delft), and that’s what led me to decide to join Philips. In fact, I had no prior knowledge of healthcare design, but fortunately, there was training upon joining the company. It was during that time that I was first introduced to healthcare user experience design (Healthcare UXD). In the very first session of the training, they introduced several cases where people had died due to design errors. It made a strong impression on me—how a poorly designed healthcare product could lead to the loss of life. I felt a significant weight of responsibility.

Despite this weight, Philips was advocating for innovation at the time. They were losing market share in many consumer electronics markets to Samsung and LG. As a result, during my time at Philips, the company declared a focus on healthcare and pursued the servitization of healthcare. The service design role was established within Philips, and in-house designers were encouraged to receive service design training or transition into these positions. There was a growing consensus within the company about the necessity and justification for transitioning from physical devices like MRI, CT, and X-ray machines to healthcare services.

With society rapidly aging, a surge in medical demand, and limited medical supply, what should be done? Home care needed to be promoted, and preventive medicine had to be enhanced, making digital technology still crucial. From a preventive standpoint, the idea was that citizens would regularly submit surveys or passively collect data in their daily lives to predict illnesses before they worsened. There were also various attempts in the field of telemedicine. It was against this background that I participated in and led several projects, eventually leading to my joining UNIST.

YWP From what you’ve said, it’s clear that the role of UX in the field of medical healthcare is extremely important. A poorly designed UX can significantly impact human lives, so it must be well-designed. I particularly resonate with the fact that this critical responsibility is what drew you to start in this field. I also think that as you worked on various projects at UNIST, your interest in UX and healthcare grew, especially with other professors at the university who are also involved in UX and healthcare, which likely made the transition feel natural.

YWP I’ve seen you take on several government projects while working together, and I’ve also seen you do a lot of design and development through these government projects. Could you share one or two of the most successful examples from these projects that stand out to you, especially those that involved collaboration?

HK I am very grateful to have come to UNIST. I feel fortunate to be working on research projects with excellent collaborators. I’ve found that Korean doctors are very open and positive about research. In the Netherlands, it was very difficult to meet with MDs for research or design projects. Even at Philips, although we conducted joint research with major hospitals, on-site research was challenging, and the medical staff didn’t actually participate in the research; they typically only served as consultants. However, in Korea, MDs actively participate in the research process. It’s encouraging to be able to conduct healthcare design research in such an environment.

Recently, I’ve been focusing on digital phenotype research. This research involves predicting the mental health status of subjects using various sensors or keystroke data. We are working with collaboration teams from Asan Medical Center and Sungkyunkwan University, and we are currently collecting relevant data. Digital phenotype research is challenging because it involves many variables that are difficult to control. A key aspect of this research is conducting it in everyday settings rather than in controlled environments, which necessitates the use of big data analysis and AI-based analysis.

YWP It seems like you’re working on designs that analyze users’ mental health status using various biometric signals or smartphone usage data. Have there been any design awards or research results that have come from this work?

HK I don’t usually submit the results of research projects for design awards. I agree with the idea of design award inflation. Twenty years ago, design awards held significant authority, but nowadays, I feel their prestige has diminished. While design awards still receive entries from over 100 countries, most of the winning designs come from countries or companies with strong design education. For various reasons, I encourage students to submit to design awards as a way to wrap up projects. Having a specific goal, like aiming for a design award, can be helpful when creating portfolio projects.

YWP The reason I asked is that the research results from government projects need to be well summarized and packaged so they can be communicated to others—like company stakeholders, researchers, and designers—who can then apply them to their own projects. I think design awards, beyond being a matter of prestige for designers, are effective because they present results through five poster images, short texts, and videos that are nicely displayed on accessible websites and in booklets. These serve as valuable resources for anyone interested in design or research. From that perspective, I’m curious about how you plan to disseminate the results of your digital phenotype-based healthcare UX research, especially the outcomes of your government projects.

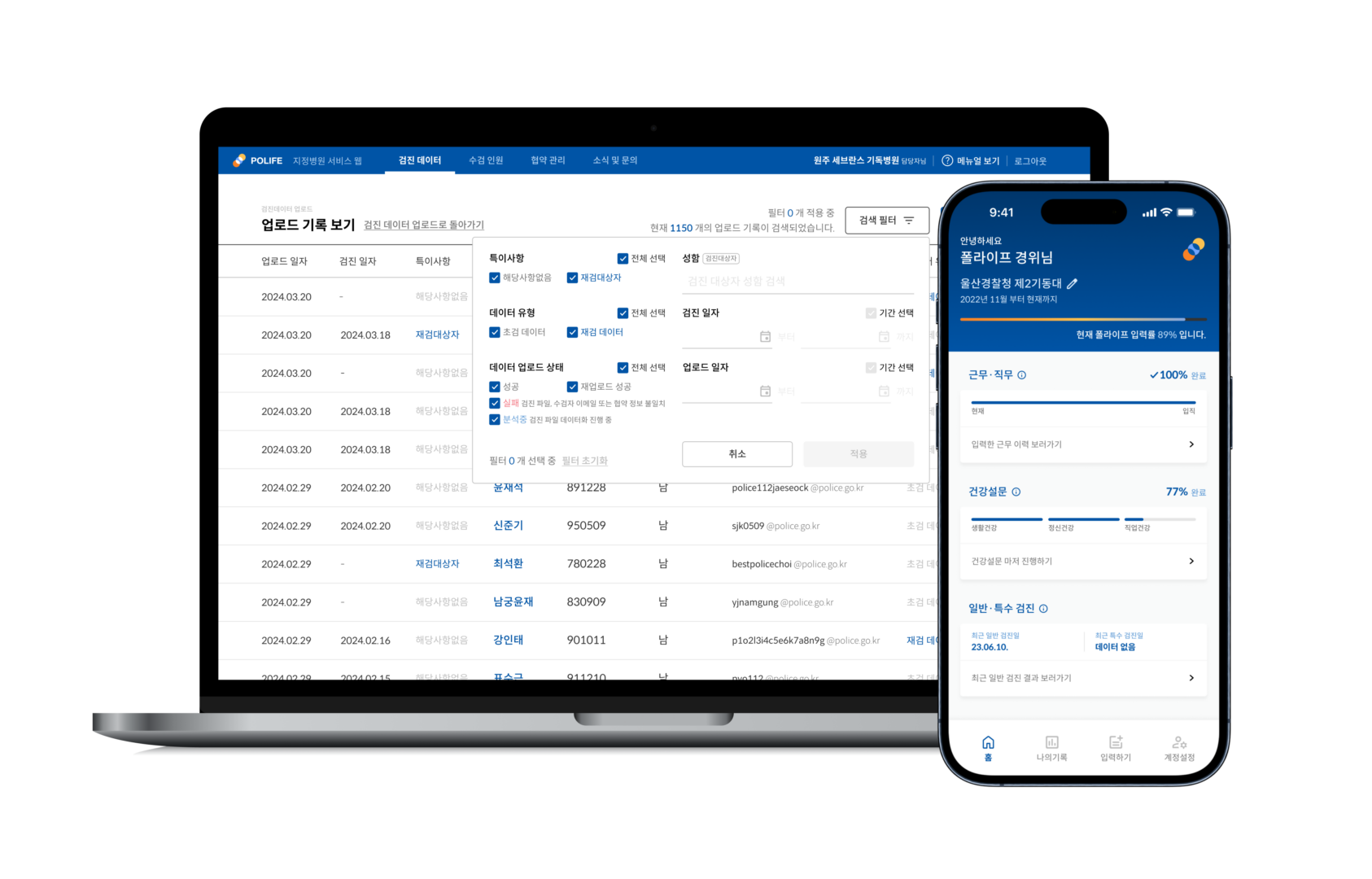

HK In the case of the police health management platform project that our lab is working on, it was designed so that 200,000 police officers would actually use the research results. If users don’t see clear value in a service, they won’t use it. So, a major focus for our lab is figuring out how to transform research projects into something that has real user value. How can we encourage users to voluntarily use the service, and if they are required to use it, how can we minimize resistance to the mandatory nature of the service?

We gave this a lot of thought, and for the police health management project, we identified ‘injury claims’ as the core element. Policing is one of the most challenging jobs when it comes to health management because different roles expose officers to different hazards. For instance, traffic police are heavily exposed to fine dust, while those investigating serious crimes are often exposed to trauma. If police officers use the platform we developed, it will track and record the changes in their job roles over a long period of time.

As a result, even if their duties change over the years, their health records related to each role will remain on the platform. This means that, if any issues arise after retirement, they can use the data recorded on the platform to make claims. When we communicated this user value, police officers finally understood why they should use the service and began to do so. The police health management platform can be seen as a successful case where our lab made a significant contribution.

YWP So, it seems like one of the strategies we’re discussing to increase engagement is akin to a rewarding system, right? Essentially, people are more likely to use the service if there’s a tangible reward for them, and in this case, that reward is the injury claim.

HK Yes, but even when it comes to rewards, users care about whether the reward is genuinely beneficial for them. That’s why we put a lot of thought into this aspect, and I often emphasize to our researchers that our lab, OND, should always focus on pursuing user value

YWP I have a quick question. You mentioned earlier that if you could go back, you’d still choose to do what you love. How do you plan to advise your students on this matter?

HK The guiding principle at OND Lab is to align with what the students want and the direction they wish to take. I always encourage them to follow their desired path. Lately, I’ve been reflecting a lot on my role as a “practical professor” and what I should be doing. I believe part of my responsibility is to ensure that UNIST Design students are well-prepared to be competitive in the job market. Although our students are already doing well, I keep thinking about how we can enhance their competitiveness further. This is also why we focus so much on preparing for design awards with the students.

YWP Lastly, do you plan to continue your research on design using digital phenotyping for real-life programs, like those for the police or fire departments? Or are you considering other areas of design or research for the future? If you have any thoughts on your future direction, please share them with us as we wrap up.

HK The field of design is changing rapidly. Even in academia, the discourse on sustainability is becoming more important. We’re seeing a shift from human-centered design to life-centered design, which focuses on entities beyond just humans. The related philosophy even extends beyond life to consider objects as subjects of contemplation. I’ve also been thinking a lot lately about how to move away from human-centered approaches.

In these times of rapid change, it’s important not to confine oneself but to remain flexible and open to new ideas. This is something I see as crucial for students as well. UNIST Design seems well-positioned to nurture open-minded talent. However, when students focus on Future Design, it might not always immediately shine in the current market. UNIST’s educational approach aims to develop students who can become societal leaders beyond just the design industry, promoting design leadership education. But this focus might mean that our students could lack certain skills needed to compete directly in the market.

So, the challenge is how to use our limited time and resources to ensure that our students are not only competitive now but also able to develop leadership skills for the future. UNIST Design is a very young department, and I hope that as we produce more graduates in the future, they will be able to have an impact within the design society.

YWP Thank you so much for your honest answers and deep insights. This has been a thought-provoking hour for me as well. Hope we could have such discussion in near future.

HK Thank you for the good questions. Likewise!