HCI Research and Design: Interview with Professor Ian Oakley

Interviewed by Seungho Park-LeeYou can find the Korean version of this page here.

이 페이지의 한국어 버전은 여기에서 찾을 수 있습니다.

In this Interview, we meet Ian Oakley, a full professor in Human Computer Interaction (HCI) at UNIST Design. This interview was done over Zoom on Fri Sep 17 and in this abridged version, we explore the life of an HCI researcher and the relevance of the field to design through papers professor Oakley and his team produced.

Seungho Park-Lee (SPL) Thanks for agreeing to do this interview, and I am so excited to have you as the first faculty to talk about our work in UNIST Design. I know you are a human-computer interaction (HCI) researcher. But can you say a few words about what you do for our readers?

Ian Oakley (IO) Thanks for having me. Sure, I often call what I do ‘nuts-and-bolts’ HCI – research that focuses on the basics of how people operate digital technology. To give an example, many of us use computers everyday, and when we do it is often with devices like the computer mouse. But this everyday object has a very specific, and quite unique form and function – how was it imagined? How was it designed? Who created it?

It turns out that the mouse was invented by Douglas Engelbart, a scientist and early HCI visionary. He famously demonstrated it, alongside many other innovations, in a video dubbed the “The Mother of All Demos” back in 1968. Engelbart was motivated by the potential of computers to support their users – to augment their intellect, to use his own terminology. Devices like the mouse were created to fulfill a specific part of this vision: to make it easier for people to control computers. My work continues this tradition and, at its most general, focuses on designing, developing, evaluating and discussing new ways of interacting with and controlling digital systems.

One reason these perspectives are still relevant is that today’s digital environment is highly diverse. In addition to computers, there are IoT systems, mobile devices, wearables and more. Technologies well suited to one setting will not necessarily apply to another – using a mouse to control a smartwatch would be odd to say the least! My work explores technologies and designs that enable people to operate all kinds of digital devices expressively, effectively and efficiently. I’m sure you have used your phone or smartwatch and sometimes found it frustrating – maybe there have been persistent errors while you type, or you become lost in the deep menus of an app or have found that key features you want are unavailable or just plain hard to access. I see these problems as opportunities for design. By creating input and interaction technologies that can better meet people’s needs and expectations, we can create digital systems, in all manner of form factors, that can empower and enable them.

SPL Fascinating. How did you become interested in what you do?

IO Human-computer interaction? I always had an interest in the intersection between people and computers. My undergraduate major combined psychology and computer science – going in, I saw artificial intelligence as the overlap between computers and people. But the university I studied at, the University of Glasgow, did not have a strong AI focus at that time. Rather they had a leading research group in HCI and, over the years of my studies, this drew me in and sparked my interest. We are all the product of both our intentions and our environments, I guess.

SPL I totally get it. I was in Aalto University where human centered design is very strong, and I became part of that community. I’ve looked through some of the papers you’ve written, and it seems that there has been a slow shift in what you do. For example, your 2000 CHI paper, Putting the Feel in ‘Look and Feel’, seems more abstract and somewhat theoretical and your 2018 UIST paper, Desiging Socially Acceptable Hand-to-Face Input, has stronger practical implications. How do you see this change yourself?

IO I do not think what I do has changed much at heart. My work focuses on exploring the consequences and implications of new forms of interactive technology. The 2000 paper was actually written while I was doing my PhD. We were inspired by Bill Gaver’s work on auditory icons that used sound to represent physical properties. In Gaver’s work, clicking on an icon would trigger a sound based on the contents of the file. For example, a large video file might produce a deep thunk, as if you had knocked on a heavy piece of wood. On clicking on a short video clip would play a light tapping, as if you touched something thin and light. We sought to explore similar ideas of physicalization, but used haptics, or the sense of touch, rather than sound. We took a force-feedback device, basically a little robot arm that can push you, so that you can physically feel virtual objects on a computer. This type of device is commonly for things like training – imagine a doctor practicing on a virtual body they can feel as well as see. In our work, we asked people to control a cursor on a computer screen and applied different physical sensations to buttons – they could be recessed, sticky, rough, or magnetic. We catalogued and documented the outcomes of this idea – basically that it works well if there is a single button, but that all the feedback competes when there are many buttons. It can get overwhelming.

SPL But how about your 2018 paper on socially acceptable hand gestures? Would you say that it’s more geared towards the interaction between people and people, or people in different cultures? Of course, this is similar to other papers in that it involves the sensing and technical aspects, but at the same time, the result can be highly culturally situated in that some gestures are more acceptable in some cultures than another.

IO True. In that paper, we are trying to understand the input space for HMDs.

SPL Oh, what is a HMD?

IO Head mounted display.

SPL You see, your field and mine are so far away, HMD is a word in your daily discussion, and I don’t even know what it is short for (laugh).

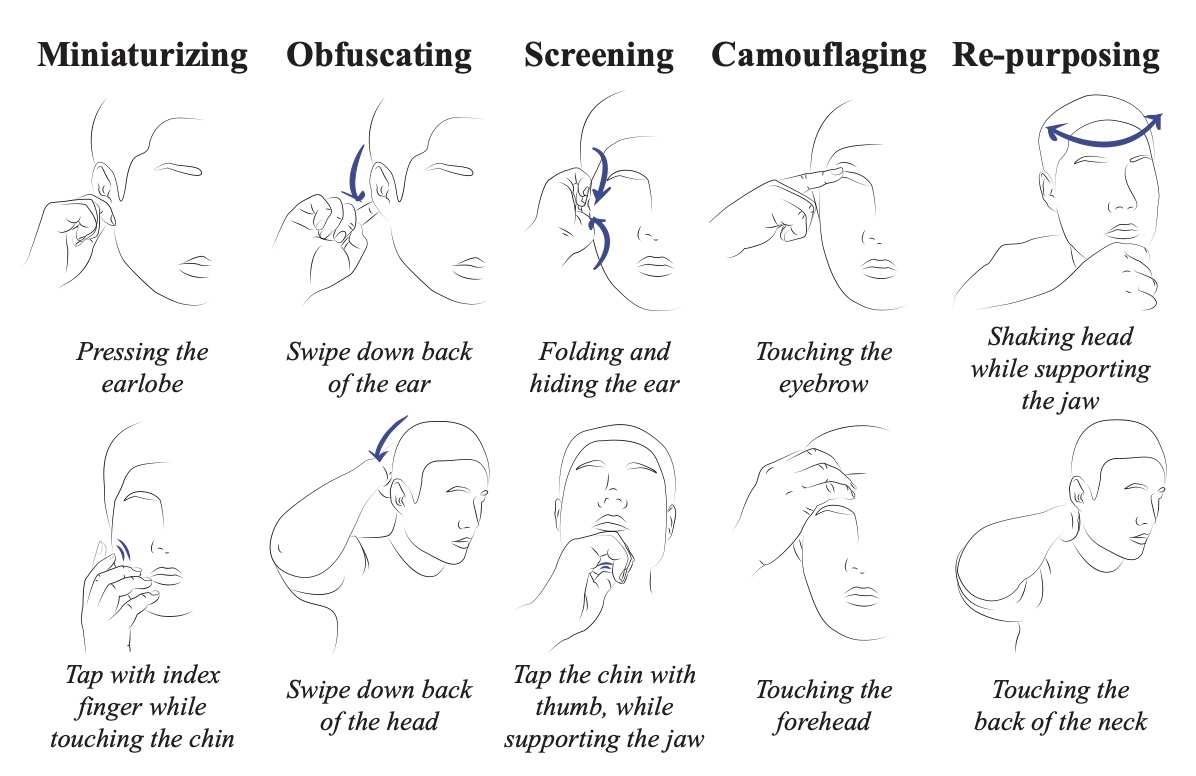

IO The commercial ones are relatively recent, but the terminology has been with us for decades. We cannot say Head Mounted Display all the time, that’s too long (laugh). But regardless of what you call them, one of the most common ways to control an HMD is via hand gestures – basically by waving your hands around. For example, the original Microsoft HoloLens had its users open their fingers in front of their faces to open a menu. This is fine for a device used in a home or even an office environment, but what about more public spaces like the bus or metro? Making such large-scale gestures in public may make people feel awkward or uncomfortable. Looking forward to a future where these devices might replace smartphones – become the next norm – we wanted to explore how people could control them in ways that would be more socially acceptable in public.

SPL Interesting, and that’s true the norms change over time with technological advances, and they evolve globally.

IO Definitely. I am old enough to remember the time when it was unacceptable to send text messages on your phone while socializing with a group in a bar or cafe. It was considered rude. Nowadays people do this all the time. Talk to each other, check their emails, browse and post on Instagram. But today most people still do not feel comfortable talking to their voice assistant over bluetooth earphones – speaking out loud to their device makes them uncomfortable. However, some are doing it. I just saw one person today actually. This may become the next norm.

SPL That is so true.

IO And while people using HMDs in public spaces is not yet common, one way we might be able to make input on these devices more familiar and less strange is by adapting the kinds of behaviors people already perform in public. Think about how we read and swipe on our phones while riding the subway. It’s really not too different from how people read books or newspapers. This similarity made the transition to using phones in public quite straightforward. It didn’t involve any strange or new behaviors. Likewise, people touch their faces all the time, it is a really common and socially acceptable behavior. We’ve probably both done it a dozen times during the course of this interview. So in this paper we explored how these commonly occurring touches could be repurposed to make input on an HMD, trying to find a sweet spot between movements that people felt comfortable performing and those we could sense and use to control a device. We eventually settled on touches to the ear or those that could be hidden within the hand, as these touches involve subtle motions and offered people a degree of privacy in their interactions.

SPL So from your perspective, what is design, or how HCI is relevant to design?

IO In the end, envisaging and then moving towards desired future states. HCI is a user- and future-focused discipline, which lies at the core of why it is associated with design. HCI projects, in general, develop novel interaction concepts or prototypes, or explore the implications of such artifacts. There are many elements where HCI and design overlap, and the most important thing, in my opinion, is that we are trying to explore and create something new – which is how we create value.

SPL How do you find inspiration for your research?

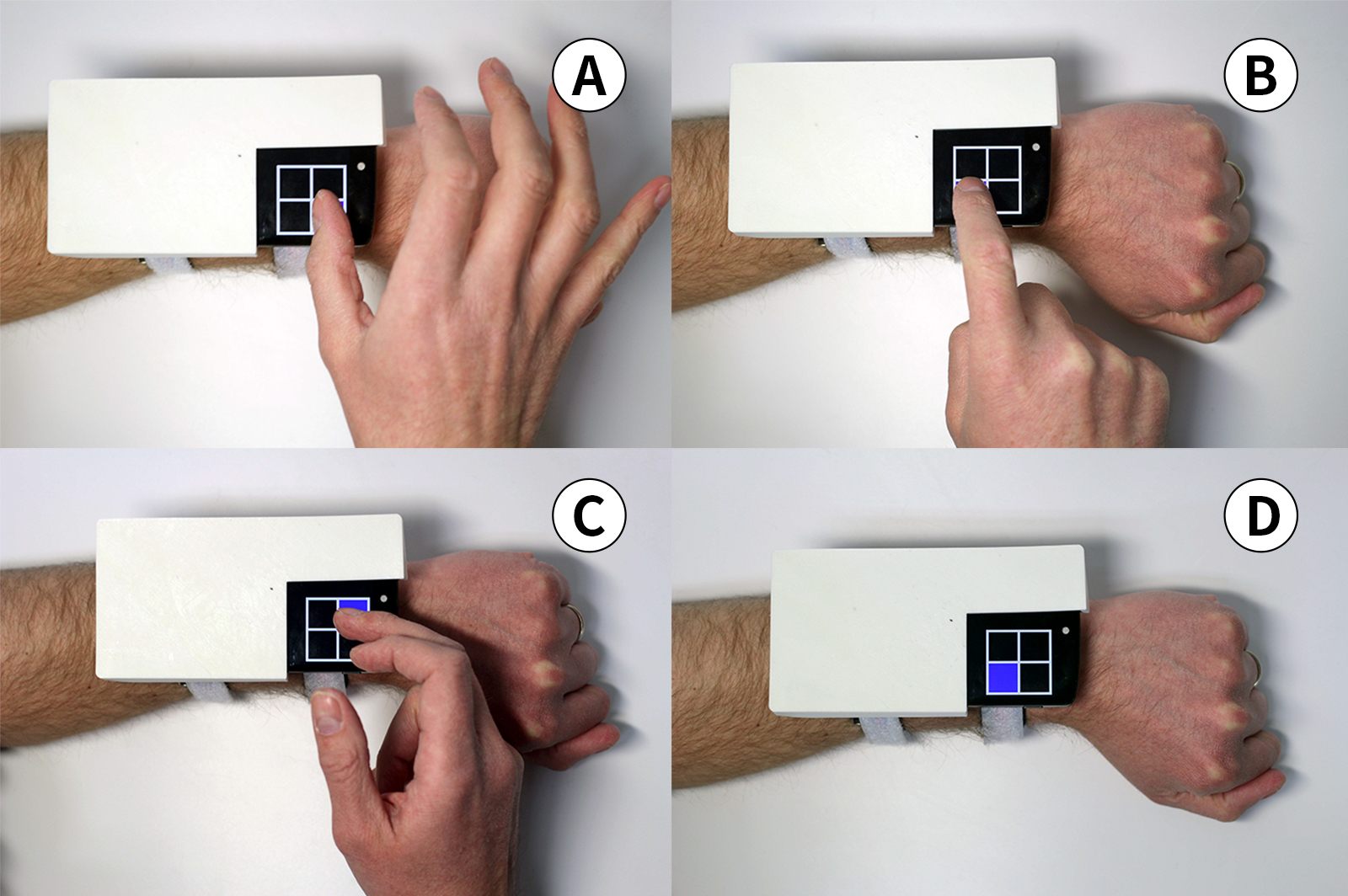

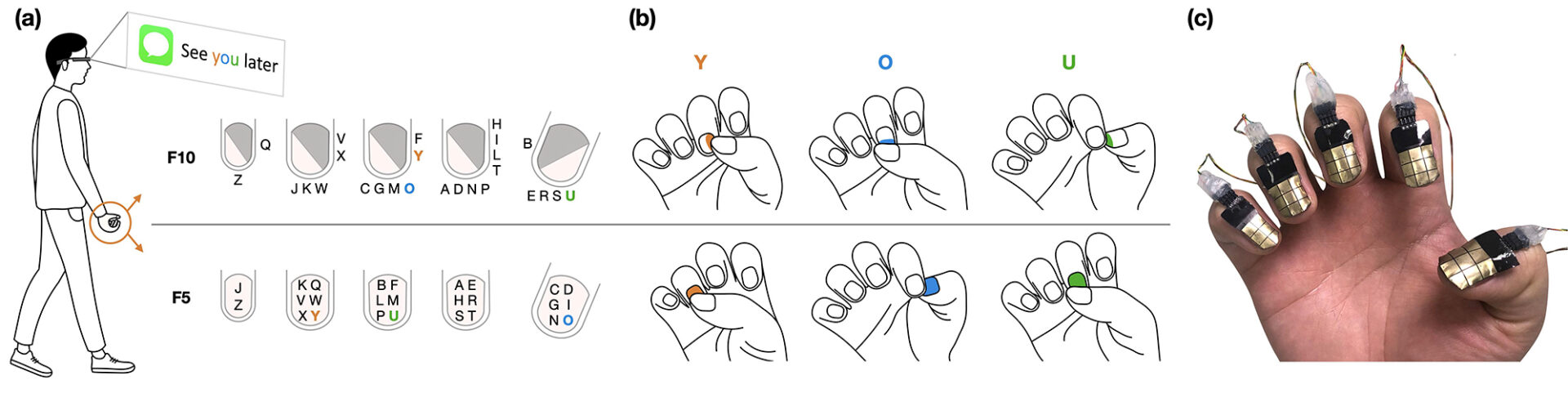

IO I’d say, expertise, opportunism, and interdisciplinarity. Of course, you need to know a fair amount about what has been studied before. Otherwise you try to solve trivial problems or those that are already well addressed – we all stand on the shoulders of giants after all. Then comes opportunism. One great thing about HCI is that it readily embraces new technology. A few years ago, there were no smart watches. Now they have become popular, bringing with them a whole host of new and unique problems, like their small screens, and opportunities, like novel application scenarios such as fitness tracking, for HCI researchers to study. Fast forward to the present day and HMDs and smart glasses are rapidly emerging as a platform. These bring yet another set of new issues for HCI researchers to sink their teeth into. Finally, interdisciplinarity. HCI is a very welcoming field that frequently embraces and integrates methods from diverse sources. We often find strong value in exploring how approaches from other fields can be applied to HCI problems. For example, we recently published work on text entry that used computational methods to derive an optimal solution to the problem of how to arrange the keys on a new type of wearable keyboard. By integrating these methods with our existing practices we were able to create a stronger research project.

SPL A lot of the discussions we had today seem applicable to industry. We see new devices every year, and as you said, each requires new forms of interaction. It looks like your results may be also used in future digital devices. So, how does that really pan out? Do companies sometimes approach academics, do they hire people?

IO Definitely. Some students get approached by companies when they publish interesting papers that are relevant to the technologies companies are developing. One of my students recently experienced such a case, although it didn’t lead to a hire. So it’s clear that companies pay attention to academic papers – in fact, companies like Google or Microsoft maintain strong HCI research groups and participate very actively in HCI research communities by publishing papers and funding research projects. There’s also a widespread acknowledgment that academic HCI work gets used by companies implicitly – I can trace most new interactive features I see on a digital device back to an academic paper.

I think it’s unfortunate that companies don’t do more to overtly and explicitly acknowledge these links to academic research. Rather than impacting individuals, the lack of acknowledgment hurts the field of HCI as a whole – much of what we do is used by billions of people on a day-to-day basis, but public perception of our work is somewhat overlooked. This leads to a systematic under-rating of the importance of HCI research. For example, while the new features on a next generation smartphone might generate a lot of press and excitement, the HCI research that underpins such features has a much lower profile. As academics we need to do more to raise the profile of our field and ensure a wider appreciation of the value and impact of our work on the world.

SPL Interesting. I hope there will be more people who appreciate your work and of the community more broadly. Thank you so much for the time, and for sharing your thoughts!

IO Sure, any time!